Back to Homepage |

|

GOSNOLD: 1602

edited by Karle Schlieff

whereunto said Editor

hath appended

Special Feature Topics

(The Auk, Sassafras, Swidden, and Calendric Differences)

Contact Karle Schlieff via this website to obtain a hard copy.

"We stood awhile like men ravished at the beauty and delicacy of this sweet soil; for besides diverse clear lakes of fresh water (whereof we saw no end), meadows very large and full of green grass --- even the most woody places (I speak of only of such I saw) do grow so distinct and apart, one tree from another, upon green grassy ground, somewhat higher than the plains, as if Nature would show herself above her power, artificial….”

from the Editor’s Introduction

May 25, 1602, New Style: 42 degrees N. Latitude; 70 degrees 15 min. W. Longitude

The crew of the small English bark Concord had been at sea for over seven weeks. Forty-eight hours ago they had finally acquired the northeast coast of America. Yesterday they met a group of Indians in a small European boat, a shallop, who kindly drew them a chalk map of the coast. The English took their leave and continued southward on a fresh breeze.

This morning they entered a huge bay encircled by a mighty headland. It took them all day to piece together the clues that the headland at the east, was connected to the mainland on the west, an enormous cape. The leader of the expedition with a few others took the shallop out to explore the nearby shore, it was a hot and humid day in late spring. In his absence the crew had practically pestered the ship with cod. They caught so many and in so little time that they started to throw them back just to make room on the thirty-ton ship. When their leader returned from his reconnaissance, the ebullient crew, gorged on fresh cod, pleaded with him to do the right thing.

He did. On May 25, 1602, New Style, mid-afternoon, Captain Bartholomew Gosnold wrote in his log the new name for the vast cape, Cape Cod.

This story is about the voyage of an English explorer, unknown at the time, who came to New England and left several important place names as well as three documents describing the voyage. A fourth document from Sir Walter Ralegh also survives. In it he complains to the Principal Secretary of State about Gosnold’s infringement on his monopoly patent for America.

The goals of Gosnold’s voyage seem varied, maybe too ambitious. He wanted to find Verrazanno’s famous Refugio (Narragansett Bay, 1524) and plant a colony or trading post there. To offset the heavy expenses and to turn a profit, Gosnold needed to collect as much New World treasure as the returning ship could hold. Of course this meant gold, if it could found. But Gosnold would settle for furs and sassafras, especially sassafras: it was a wonder drug in Europe and obtainable only in the New World.

It was easy to find and returned a fabulous profit. Gosnold’s father at this time was in serious trouble with debts. He was languishing in the debtor’s prison at Southwark. Who knows --- Obtaining financial relief for his father may have been the main objective for the whole voyage. A competing theory is that the voyage was planned by a loose consortium around Captain Gilbert and that Gosnold attached himself to the voyage at the last minute through mutual friends.

Gilbert was a minion of Lord Cobham, who may have obtained an old unused license, issued by Ralegh to Edward Hayes, to make an expedition. Lord Cobham was the brother-in-law to Robert Cecil, the Principal Secretary of State for Queen Elizabeth. This theory goes a long way to explain why Gilbert did not have the rations onboard for a small trading post to winter over in America. But, since both the Archer and Brereton accounts of this voyage relate how Gosnold was the undisputed leader, the truth probably lies somewhere in between.

On March 26, essentially New Year’s day of 1602 in the old Julian calendar, the Concord, a small 30-ton bark of Dartmouth, left Falmouth. On board were:

Captain Bartholomew Gosnold, the leader of the expedition: his plan was to stay Captain Bartholomew Gilbert, the captain of the Concord, out and back;

John Brereton, chaplain on and a friend of Gosnold: he wrote an account;

Gabriel Archer, a lawyer and friend of Gosnold; he wrote an account;

William Strete, master of the ship, possibly owner or part-owner of the Concord;

Tucker, whose shock names the shoals off Monomoy “Tucker’s Terror”;

A man named Hill, for whom Mr. Archer names an island, Hills Hap;

Mr. Robert Meriton, who found the first sassafras trees, according to Brereton;

Mr. Robert Salterne, whom Pring’s 1603 Relation reports with Gosnold);

John Angell, likewise mentioned in Pring’s Relation;

John Martin (at least according to historians Belknap and Brown); and

21 other men, names unknown.

We know from the documents that there were eight sailors and that twelve others would return with the ship. The rest, twelve, would remain at the trading post: thirty-two people in all, according to Brereton. Archer says Gosnold was accompanied by thirty-two, implying thirty-three in all.

Gosnold’s voyage stepped on the toes of Ralegh, the patent holder of English America, and the monopoly holder of the sassafras market. Gosnold did not have Ralegh’s explicit permission to go to his lands in America. A deal was struck when Gosnold got back to England. They would print the Brereton relation as a popular account with a glowing dedication to Ralegh to help him to save face, and serve the immediate purpose of an inspirational tract.

England needed to inspire the seamen-privateers away from plunder and into exploration and colonization. Hakluyt was in all probability known to Gosnold, Brereton, and Archer: they all lived within a few miles of each other. We know Gosnold has read Hakluyt’s books and most likely consulted him prior to the voyage. An editor for Brereton’s story was needed. One with experience. One who knew what to leave in and what to leave out.

Brereton’s printed relation is thirteen pages, about 3500 words and only 63 long run-on sentences. It is lyrical, upbeat, and full of promise. It follows the classic Hakluyt formula: stress the good news, leave out all the maritime details, make lists of desirable animals and trees, and leave it to the reader to say: I wish I was there. It is a not a heavy-handed propaganda piece. It tells a great story without a lot of those pesky details, the kind that a competitor, a seaman, or an historian could use.

The possible first editors were Captain Edward Hayes (of The Golden Hind) whose fifteen year-old treatise on colonization was appended to the second “impression” of Brereton’s relation; Thomas Harriot, who was closely aligned with Ralegh; and of course, Richard Hakluyt. Historian David Beers Quinn theorizes that Brereton himself may have been a protégé of Hakluyt and produced the book himself to Hakluyt’s exacting specifications: narrative-parsing, incorporating others’ specimen lists, leaving out the maritime details and so on.

Archer’s relation, which is more detailed, was also delivered to Hakluyt sometime before 1607 (probably late 1602). We know this because Archer goes to Virginia in 1607 and dies there in 1610. He did return briefly to England in 1608, but his time was consumed with organizing the second charter for Jamestown and getting back as soon as possible with the new management.

Hakluyt died in 1616, but passed on his whole life work, including Archer’s relation, to Samuel Purchas, who finally published the Archer relation in 1625, twenty-three years after Gosnold’s voyage and five years after the Pilgrims sailed into New Plimoth. It served the people in power to suppress certain information.

Suppression of information? Bear this fact in mind: the only relation of the next voyage to New England in 1603, Martin Pring’s, was also published for the first time by Purchas only in 1625. Pring was actually at New Plimoth in 1603, entertaining the Patuxet Indians with a guitar and occasionally terrorizing them with two huge mastiffs, Fool & Gallant. And all this seventeen years before Bradford, Standish, and Brewster. In any case, the original detailed journals of Archer and Brereton, as well as the Concord’s log, are all lost.

Today there are ghosts out in the ocean off modern-day Chatham. They are submerged memories. Ghost Islands. They were real enough in 1602. Gosnold, Champlain, Smith, and others describe them, Seal Island, Webbs Island --- Time and storms have scrubbed them into nothing but waves. But then as now, the area south of Chatham is foul: over one hundred square miles of shoals, rips, and breaches.

It was at this point in the voyage when a man named Tucker was on lookout duty (some say John, some say Thomas, though it is really unknown). The tide was running out to sea, slowly revealing the dangers. What he saw sent shivers through him. All around the ship was white water --- Shoals! It would be the death of them all. Tucker was probably screaming at the top of his lungs.

The master of the ship, William Strete, with crisp orders to his crew, somehow managed to steer through the dangers; by no means an easy feat with a square-rigged ship. When they were safe, Captain Gosnold made it known to all aboard that these shoals were to be known as Tucker’s Terror. It is worth noting that Brereton’s edited relation states that this coast is “as free of obstacles as any,” and that from the time they left Cape Cod Bay to their arrival at Capawac/Martha’s Vineyard, a mere half-sentence of description survives the editing. Gosnold aptly named the point near the Terrors, Point Care: today we call it Monomoy Point.

Gosnold and Archer went on to be leaders at the very beginning of Jamestown in 1607. Brereton disappeared from the records. Ralegh was soon jailed in the Tower of London by King James, mainly to get him out of the way. Brereton’s relation saw two editions within months of their return --- a 17th century bestseller. The power of the written word spawned a follow-up trip by Martin Pring at the next possible launch window: early 1603. Pring even took two of Concord’s veteran crew with him. Pring knew that there was a tidy “little house and fort” on the other side of the Atlantic. He also knew that there was more valuable cargo there, for the taking.

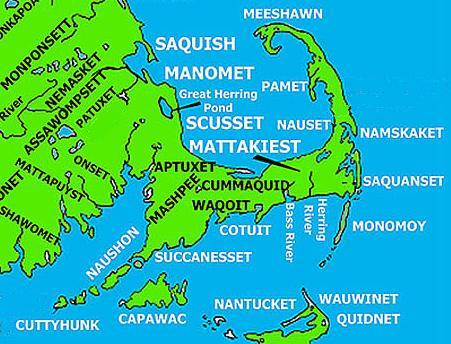

Bartholomew Gosnold and the crew of the Concord left behind a few things in New England. The very least are place names, durable markers on the map: Cape Cod, Martha’s Vineyard, and the Elizabeth Isles. The real legacy of the voyage, a gift to all who read their texts, is the promise of exploration, a simple example of courage and hope. Gosnold’s Hope.

What follows is the complete Brereton text, spelling-modernized, and without the “treatise” by Mr. Hayes --- as we need no “inducements” to plant in these parts.

Enjoy!

Your wellwisher,

Karle Schlieff

***

A BRIEF AND TRUE RELATION

OF THE DISCOVERY OF THE NORTH PART

OF VIRGINIA;

being a most pleasant, fruitful and commodious soil:

Made this present year 1602

by Captain Bartholomew Gosnold,

Captain Bartholomew Gilbert, and diverse other gentlemen

and their associates, by the permission

of the honorable knight,

Sir Walter Ralegh, &c.

Written by M. John Brereton, one of the voyage;

whereunto is annexed a Treatise of M. Edward Hayes,

containing important inducements

for the planting in those parts,

and finding a passage that way to the South Sea, and China.

With diverse instructions of special moment newly added

in this second impression.

LONDINI,

Imperis Geor. Bishop

1602.

To the honorable Sir Walter Ralegh, Knight, Captain of her Majesties Guards, Lord Warden of the Stanneries, Lieutenant of Cornwall, and Governor of the Isle of Jersey.

Honorable sir, being earnestly requested by a dear friend to put down in writing some true relation of our late performed voyage to the North parts of Virginia, at length I resolved to satisfy his request, who also emboldened me to direct the same to your honorable consideration; to whom, indeed, of duty, it pertains.

May it please your Lordship therefore to understand, that upon the six and twentieth of March 1602, being a Friday [April 5, 1602, New Style], we went from Falmouth, being in all, two & thirty persons, in a small bark of Dartmouth, called The Concord, holding a course for the North part of Virginia; and although by chance the wind favored us not at first as we wished, but enforced us so far to the Southward, as we fell with S. Marie, one of the islands of the Azores (which was not much out of our way) but holding our course directly from thence, we made our journey shorter (than hitherto accustomed) by the better part of a thousand leagues , yet were we longer in our passage than we expected; which happened, for that our bark being weak, we were loathe to press her with much sail; also, our sailors being few, and they none of the best, we bare (except in fair weather) but low sail; besides, our going upon an unknown coast, made us not over-bold to stand in with the shore, but in open weather; which caused us to be certain days in sounding, before we discovered the coast, the weather being by chance, somewhat foggy.

But on Friday, the fourteenth of May [May 24, 1602, New Style], early in the morning, we made the land, being full of fair trees, the land somewhat low, certain hummocks or hills lying into the land, the shore full of white sand, but very stony or rocky. And standing fair alongst by the shore, about twelve of the clock the same day, we came to an anchor, where eight Indians, in a Basque shallop with mast and sail, an iron grapple, and a kettle of Copper, came boldly aboard us, one of them appareled with a waistcoat and breeches of black serge, made after our sea-fashion, hose and shoes on his feet; all the rest (saving one that had a pair of breeches of blue cloth) were naked.

These people are of tall stature, broad and grim visage, of a black swart complexion, their eyebrows painted white; their weapons are bows and arrows. It seemed by some words and signs they made, that some Basques, or of Saint John de Luz, have fished or traded in this place, being in the latitude of 43. Degrees [near Cape Porpoise, Maine]. But riding here, in no very good harbor, and withal, doubting the weather, about three of the clock the same day in the afternoon we weighed, & standing Southerly off into sea the rest of that day and the night following, with a fresh gale of wind, in the morning we found ourselves embayed with a mighty headland ; but coming to an anchor about nine of the clock the same day, within a league [3 miles] of the shore, we hoisted out the one half of our shallop, and captain Bartholomew Gosnold, myself, and three others, went ashore, being a white sandy and very bold shore; and marching all that afternoon with our muskets on our necks, on the highest hills which we saw (the weather very hot), at length we perceived this headland to be parcel of the main, and sundry Islands lying almost round about it.

So returning (towards evening) to our shallop (for by that time, the other part was brought ashore and set together), we espied an Indian, a young man, of proper stature, and of a pleasing countenance; and after some familiarity with him, we left him at the seaside, and returned to our ship; where, in five or six hours absence, we had pestered our ship so with Cod fish, that we threw numbers of them over-board again: and surely, I am persuaded that in the months of March, April, and May, there is upon this coast, better fishing, and in as great plenty, as in Newfound-land: for the schools of Mackerel, herrings, Cod, and other fish, that we daily saw as we went and came from the shore, were wonderful; and besides, the places where we took these Cods (and might in a few days have laden our ship) were but in seven fathom water [42 feet], and within less than a league of the shore: where, in Newfound-land they fish in forty or fifty fathom water [240-300 feet], and far off.

From this place, we sailed round about this headland, almost all the points of the compass, the shore very bold: but as no coast is free from dangers, so I am persuaded, this is as free as any. The land somewhat low, full of goodly woods, but in some places plain. At length we were come amongst many faire Islands, which we had partly discerned at our first landing; all lying within a league or two one of another [3-6 miles], and the outermost not above six or seven leagues [18-21 miles] from the main: but coming to an anchor under one of them, which was about three or four leagues [9-12 miles] from the main, captain Gosnold, my self, and some others, went ashore, and going round about it, we found it to be four English miles in compass, without house or inhabitant, saving a little old house made of boughs, covered with bark, an old piece of a weir of the Indians to catch fish, and one or two places where they had made fires.

The chiefest trees of this Island, are Beeches and Cedars; the outward parts all overgrown with low bushy trees, three or four foot in height, which bear some kind of fruits, as appeared by their blossoms; Strawberries, red and white, as sweet and much bigger than ours in England: Raspberries, Gooseberries, Hurtleberries, and such an incredible store of Vines , as well in the woody part of the Island, where they run upon every tree, as on the outward parts, that we could not go for treading upon them: also, many springs of excellent sweet water, and a great standing lake of fresh water, near the seaside, an English mile in compass, which is maintained with the springs running exceeding pleasantly through the woody grounds which are very rocky. Here are also in this Island, great store of Deer, which we saw, and other beasts, as appeared by their tracks; as also diverse fowls, as Cranes, Hernshawes [herons], Bitters, Geese, Mallards, Teals, and other fowls, in great plenty; also, great store of Peas [Beach-pea], which grow in certain plots all the Island over.

On the North side of this Island we found many huge bones and ribs of Whales. This Island, as also all the rest of these Islands, are full of all sorts of stones fit for building; the sea sides all covered with stones, many of them glistening and shining like mineral stones, and very rocky: also, the rest of these Islands are replenished with these commodities, and upon some of them, inhabitants; as upon an Island to the Northward, and within two leagues of this; yet we found no towns, nor many of their houses, although we saw many Indians, which are tall big boned men, all naked, saving they cover their privy parts with a black tewed [tanned] skin, much like a Black smiths apron, tied about the middle and between their legs behind: they gave us of their fish ready boiled, (which they carried in a basket made of twigs, not unlike our osier) whereof we did eat, and judged them to be fresh water fish: they gave us also of their Tobacco, which they drink [that is, smoke] green, but dried into powder, very strong and pleasant, and much better than any I have tasted in England.

The necks of their pipes are made of clay hard dried, (whereof in that Island is great store both red and white) the other part is a piece of hollow copper, very finely closed and cemented together. We gave unto them certain trifles, as knives, points, and such like, which they much esteemed. From hence we went to another Island, to the Northwest of this, and within a league or two of the main, which we found to be greater than before we imagined, being 16 English miles at the least in compass; for it contains many pieces or necks of land, which differ nothing from several islands, saving that certain banks of small breadth, do like bridges, join them to this Island.

On the outsides of this Island are many plain places of grass, abundance of Strawberries & other berries before mentioned. In mid May we did sow in this Island (for a trial) in sundry places, Wheat, Barley, Oats, and Peas, which in fourteen days were sprung up nine inches and more. The soil is fat and lusty, the upper crust of gray color; but a foot or less in depth, of the color of our hemplands in England; and being thus apt for these and the like grains; the sowing or setting (after the ground is cleansed) is no greater labor, than if you should set or sow in one of our best prepared gardens in England. This Island is full of high timbered Oaks, their leaves thrice so broad as ours; Cedars, straight and tall; Beech, Elm, holly, Walnut trees in abundance, the fruit as big as ours, as appeared by those we found under the trees, which had lain all the year ungathered; Hazelnut trees, Cherry trees, the leaf, bark and bigness not differing from ours in England, but the stalk bears the blossoms or fruit at the end thereof, like a cluster of Grapes, forty or fifty in a bunch; Sassafras trees great plenty all the Island over, a tree of high price and profit; also diverse other fruit trees, some of them with strange barks, of an Orange color, in feeling soft and smooth like Velvet: in the thickest parts of these woods, you may see a furlong or more round about.

On the Northwest side of this Island, near to the sea side, is a standing Lake of fresh water, almost three English miles in compass, in the middle whereof stands a plot of woody ground, an acre in quantity or not above: this Lake is full of small Tortoises, and exceedingly frequented with all sorts of fowls before rehearsed , which breed, young ones of all sorts we took and eat at our pleasure: but all these fowls are much bigger than ours in England. Also, in every Island, and almost in every part of every Island, are great store of Ground nuts forty together on a string, some of them as big as hens eggs; they grow not two inches under ground: the which nuts we found to be as good as Potatoes. Also diverse sorts of shell-fish, as Scallops, Muscles, Cockles, Lobsters, Crabs, Oysters, and Wilks [whelks], exceeding good, and very great.

But not to cloy you with particular rehearsal of such things as God & Nature hath bestowed on these places, in comparison whereof, the most fertile part of all England is (of itself) but barren; we went in our light-horseman from this Island to the main, right against this Island some two leagues off [6 miles], where coming ashore, we stood a while like men ravished at the beauty and delicacy of this sweet soil; for besides diverse clear Lakes of fresh water (whereof we saw no end) meadows very large and full of green grass; even the most woody places (I speak only of such I saw) do grow so distinct and apart, one tree from another, upon green grassy ground, somewhat higher than the Plains, as if Nature would show herself above her power, artificial.

Hard by, we espied seven Indians, and coming up to them, at first they expressed some fear; but being emboldened by our courteous usage, and some trifles which we gave them, they followed us to a neck of land, which we imagined had been severed from the main ; but finding it otherwise, we perceived a broad harbor or river’s mouth , which ran up into the main: and because the day was far spent, we were forced to return to the Island from whence we came, leaving the discovery of this harbor, for a time of better leisure. Of the goodness of which harbor, as also of many others thereabouts, there is small doubt, considering that all the Islands, as also the main (where we were) is all rocky grounds and broken lands.

Now the next day, we determined to fortify ourselves in a little plot of ground in the midst of the Lake above mentioned, where we built an house, and covered it with sedge, which grew about this lake in great abundance; in building whereof, we spent three weeks and more: but the second day after our coming from the main, we espied 11 canoes or boats, with fifty Indians in them, coming toward us from this part of the main, where we, two days before landed; and being loath they should discover our fortification, we went out on the sea side to meet them; and coming somewhat near them, they all sat down upon the stones, calling aloud to us (as we rightly guessed) to do the like, a little distance from them: having sat a while in this order, Captain Gosnold willed me to go unto them, to see what countenance they would make.

But as soon as I came up unto them, one of them, to whom I had given a knife two days before in the main, knew me, (whom I also very well remembered) and smiling upon me, spake somewhat unto their lord or captain, which sat in the midst of them, who presently rose up and took a large Beaver skin from one that stood about him, a gave it unto me, which I requited [reciprocated] for that time the best I could; but I, pointing towards captain Gosnold, made signs unto him, that he was our captain, and desirous made signs of joy: whereupon captain Gosnold with the rest of his company, being twenty in all, came up unto them; and after many signs of gratulations (captain Gosnold presenting their Lord with certain trifles which they wondered at, and highly esteemed) we became very great friends, and sent for meat aboard our shallop, and gave them such meats as we had then ready dressed, whereof they misliked nothing but our mustard, whereat they made many a sour face.

While we were thus merry, one of them had conveyed a target of ours into one of their canoes, which we suffered, only to try whether they were in subjection to this Lord to whom we made signs (by showing him another of the same likeness, and pointing to the canoe) what one of his company had done: who suddenly expresses some fear, and speaking angrily to one about him (as we perceived by his countenance) caused it presently to be brought back again.

So the rest of the day we spent in trading with them for Furs, which are Beavers, Luzernes [bobcat], Martins, Otters, Wild-cat skins, very large and deep Fur, black Foxes, Conie skins [rabbits] of the color of our Hares, but somewhat less, Deer skins, very large, Seal skins, and other beasts skins, to us unknown. They have also great store of Copper, some very red, and some of a paler color; none of them but have chains, earrings, or collars of this metal: they head some of their arrows herewith much like our broad arrow heads, very workmanly made. Their chains are many hollow pieces cemented together, each piece of the bigness of one of our reeds, a finger in length, ten or twelve of them together on a string, which they wear about their necks: their collars they wear about their bodies like bandoliers a handful broad, all hollow pieces, like the other, but somewhat shorter, four hundred pieces in a collar, very fine and evenly set together.

Besides these, they have large drinking cups made like skulls, and other thin plates of copper, made much like our own boar-spear blades, all which they so little esteem, as they offer their fairest collars or chains, for a knife or such like trifle, but we seemed little to regard it; yet I was desirous to understand where they had such store of this metal, and made signs to one of them (with whom I was very familiar) who taking a piece of Copper in his hand, made a hole with his finger in the ground, and withal pointed to the main from whence they came.

They strike fire in this manner; every one carries about him in a purse of tewed leather, a Mineral stone (which I take to be their Copper) and with a flat Emery Stone (wherewith Glaziers cut glass, and Cutlers glaze blades) tied fast to the end of a little stick, gently he strikes upon the Mineral stone, and within a stroke or two, a spark falls upon a piece of Touchwood (much like our Sponge in England) and with the least spark he makes a fire presently.

We had also of their Flax, wherewith they make many strings and cords, but it is not so bright of color as ours in England: I am persuaded they have great store growing upon the main, as also Mines and many other rich commodities, which we, wanting both time and means, could not possibly discover. Thus they continued with us three days, every night retiring themselves to the furthermost part of our Island two or three miles from our fort: but the fourth day they returned to the main, pointing five or six times to the Sun, and once to the main, which we understood, that within five or six days they would come from the main to us again: but being in their canoes a little from the shore, they made huge cries & shouts of joy unto us; and we with our trumpet and cornet, and casting up our caps into the air, made them the best farewell we could: yet six or seven of them remain with us behind, bearing us company every day into the woods, and helped us to cut and carry our Sassafras, and some of them lay aboard our ship.

These people, as they are exceeding courteous, gentle of disposition, and well conditioned, excelling all others that we have seen; so for shape of body and lovely favor, I think they excel all the people of America; of stature much higher than we; of complexion or color, much like a dark Olive; their eyebrows and hair black, which they wear long, tied up behind in knots, whereon they prick feathers of fowls, in fashion of a crownet: some of them are black thin bearded; they make beards of the hair of beasts: and one of them offered a beard of their making to one of our sailors, for this that grew on his face, which because it was of a red color, they judged it to be none of his own. They are quick eyed, and steadfast in the looks, fearless of others harms, as intending none themselves; some of the meaner sort given to filching, which the very name of Savages (not weighing their ignorance in good or evil) may easily excuse: their garments are of Deer skins, and some of them wear Furs round and close about their necks.

They pronounce our Language with great facility; for one of them one day sitting by me, upon occasion I spake smiling to him these words: How now, sirra, are you so saucy with my Tobacco? Which words (without any further repetition) he suddenly spake so plain and distinctly, as if he had been a long scholar in the language.

Many other such trials we had, which are here needless to repeat. Their women (such as we saw) which were but three in all, were but low of stature, their eyebrows, hair, apparel, and manner of wearing, like to the men, fat, and well favored, and much delighted in our company; the men are dutiful towards them. And truly, the wholesomeness and temperature of this Climate, does not only argue this people to be answerable to this description, but also of a perfect constitution of body, active, strong, healthful, and very witty, as the sundry toys of theirs cunningly wrought, may easily witness. For the agreeing of this Climate with us (I speak of myself, & so I may justly do for the rest of our company) that we found our health & strength all the while we remained there, so to renew and increase, as notwithstanding our diet and lodging was none of the best, yet not one of our company (God be thanked) felt the least grudging or inclination to any disease or sickness, but were much fatter and in better health than when we went out of England.

But after our bark [Concord] had taken in so much Sassafras, Cedar, Furs, Skins, and other commodities, as were thought convenient; some of our company that had promised captain Gosnold to stay, having nothing but a saving voyage in their minds (NOTE 28), made our company of inhabitants (which was small enough before) much smaller; so as captain Gosnold seeing his whole strength to consist but of twelve men, and they but meanly provided , determined to return for England, leaving this Island [modern Cuttyhunk], which he called Elizabeths Island with as many true sorrowful eyes, as were before desirous to see it. So the 18 of June, being Friday, we weighed, and with indifferent fair wind and weather came to anchor the 23 of July, being also Friday (in all, bare five weeks) before Exmouth.

Your Lordship’s to command,

John Brereton

***********

SASSAFRAS

Joyful News out of the New Found World!

Sassafras! The new wonder drug. And Europe was paying to get it. Sassafras trees were first found in Florida. The Indians taught the French about the Pauame tree. The French called it Sassafras. They in turn taught the Spanish, just before they tossed the French out of Florida. Here is the short list of evils that the steeped wood, and especially the roots, could cure: “all manner of diseases, without exception to any.” Very impressive, according to Nicholas Monardes, a physician of Seville, and his Joyfull Newes out of the Newe Founde Worlde (1577 edition Englished by John Frampton, merchant): in Volume 1 of 2.

Sassafras was claimed to work wonders with the lame, cure pains in the stomach, breast, and cure a toothache. Its Latin name means “stone breaker,” a possible reference to its power to cure kidney stones. Sassafras was said to provoked the flow urine (a thing 17th century physicians loved to provoke). It cured gout and pains in the joints, it cured those with “foul hands”: served warm, it caused a man to go to stool (another 17th century diagnostic), it cured the “evil of the Mother with windiness,” and it could make formerly barren women “with child.”

Most of all, sassafras was a cure for the Pox, the lues venerea. The Spanish called it the English Pox. The English called it the French Pox. The French called it the Spanish Pox. And round it went. It was syphilis, a tiny fragile bacteria that is passed by intimate contact, since it dies incredibly fast outside the warm wet environs of a living host. It was a disease of the New World and it hammered Europe, just as the Old World diseases were pounding away at the Americas. In the first years of the European outbreaks (late 1490s) it was a quick and fatal infection. Then the selfish bug and European man adapted, ever so slightly, and it became a slow ten-year dance of death. But a cure was found: take the steeped water of the Sassafras root for a “greate tyme.” It was new, expensive, and the cure came from the very source of the misery --- America! And what a market there was in Europe. Three shillings for a pound of the wood ( about $25 today) and much more for the roots. A single ship could bring back tons. And, it worked.

Or maybe it didn’t. The combination of low life expectancy in the 17th century (less than 45 years) and the apparent remission of syphilis while it silently hid in the body, liquefying the vital organs between waves of outward eruptions, made Sassafras, or any drug for that matter, look like a cure.

Sassafras is the only North American spice. The active component is safrol, a toxic liver-damaging compound if taken in huge amounts. Safrol is one of the key ingredients in the 21st century drug Ecstasy. Herbalists today still swear by Sassafras for joint pain, rashes, and gout. Sassafras, as a spice, is used in Cajun and Creole cooking in Louisiana where it is called Filè powder. (See the Internet Spice Pages of Austrian chemist Gernot Katzer.)

Today syphilis is cured in one visit and on the cheap. The Gold Standard for the last 50 years: 1.2 million units of Penicillin G (the high octane stuff, with additives) injected into each buttock.

Sassafras, after removing the potentially nasty safrol, is still the tasty ingredient in another truly American concoction: root beer.

AUKS

The Great Auk. A flightless North Atlantic penguin. The original penguin. When smaller birds like them were found in the Southern Hemisphere, the old name was extended to the new birds. They could grow to 75 - 125 pounds in weight and three feet in height.

The Great Auk’s largest nesting colony was Funk Island (Isla de Pitigoen, Island of the Penguins) off Newfoundland. The early fishing expeditions to Newfoundland, Labrador, and Greenland used them as a source of food. With a small group of men armed with clubs, they were ridiculously easy to kill on land. They were a rich source of protein, with highly nutritious fats and oils. Hungry fishermen attested to their delicious meat. And there were frillions of them.

The last recorded sighting of the Great Auk was on June 3, 1844. Museum collectors caught and killed two adult Auks on Eldey island off Iceland, and the birds were incubating a single egg at the time. The egg was supposedly smashed by the collectors because it was cracked. Other stories say it was spirited away and sold to a local apothecary by a low-level employee in the expedition, for what to him was a month’s pay.

That was it. There have been no sightings since.

Once the very presence of the Great Auks on the ocean “in numbers uncountable” was a “sea mark” indicating that the fishermen have arrived: the North American fishing banks were directly below them. Today, in all the world, there are:

81 mounted skins

24 complete skeletons

2 collections of viscera

75 intact eggs (in the Royal Ontario Museum)

This is all that remains of the millions of Great Auks. The New England Aquarium has a marvelous sculpture by John Sardonis of the last two Auks found on Eldey Island, and you can see it at The New England Aquarium.

SWIDDEN

In Thomas Morton of Merrymount’s 1637 New English Canaan, he writes: “The Salvages are accustomed to set fire of the Country in all places where they come, and to burn it twice a year, viz. at the Spring, and the fall of the leaf” (45).

All the colonists and explorers in New England noticed and wrote about the forests, the park-like forests. Large, widely-spaced trees, few shrubs, much grass and herbage. You could see for a quarter mile from any point within the forest. Amazingly, no underbrush. The English assumed that it just grew that way. They were wrong.

The Indians created these ideal habitats. They practiced a unique form of husbandry that most colonists back then did not quite understand or appreciate. The Indians fostered these “park forests” for their lifestyle and for their food supplies. They did this by burning the woods. The semi-annual fires moved quickly, burned at a low temperature, and almost never resulted in conflagrations: they were more ground fires than forest fires.

New England thicket and underbrush (here, in winter without foliage)

The fuel-load on the ground was extremely low. Contrast this to the forests of the Western United States. We have all seen the yearly and mostly futile attempts to put out these “mysterious” state-wide fires. The Indian fires recycled nutrients into the soil, created conditions favorable for berries, created more inviting animal habitat, and made travel and hunting in the forest easier. The enlarged areas, grasslands within forests, raised the total food supply.

The result was not merely to attract game, but also it created larger populations. Indian burning promoted the increase of exactly those species whose abundance so impressed English colonists; elk, deer, beaver, hare, turkey, quail, etc. The hunters also increased: eagles, lynxes, foxes, and wolves. The Indians were harvesting game and plants that they had conscientiously created. The Native peoples’ mobile lifestyle required the park forest. It confounded the settlers, who were firmly planted in a stationary farm world-view (according to William Cronon’s Changes in the Land: Indians, Colonists, and the Ecology of New England (1983: 48-52).

This innovative type of agro-forestry is always lumped under the term swidden, a.k.a. slash-and-burn. The forests today (dense, dark, forbidding) are not what they used to be (open, light, park-like). The last people to walk in a fabulous hand-tuned New England park forest were the Pilgrims. In 1617, ninety percent of the coastal New England Indian population died during an invasion by a European microbial army: influenza, chicken-pox, and measles.

Native Americans had been hermetically sealed off from Europe and Asia for tens of thousands of years and had no natural resistance to Old World diseases. The architects and caretakers of the millennia old park forests were suddenly gone. By the early 1630s, settlers called southeastern Massachusetts “ragged plain”; the underbrush literally tore at your clothes. Imagine what today’s manicured suburbia would look like if we completely abandoned a large subdivision for twenty years.

After a millennia of being held at bay, nature pounced in 1619. With alacrity and wantonness she reclaimed the wilderness and resumed her jealous experiments on flora and fauna in her dark green workshop, locked safely away behind briars, brush, and brambles.

Here is a proposal for a long-term university project: take a square mile or two of forest and apply Native American agro-forestry techniques. The first year will be the tricky, you may have to clean the brush out by hand: the fuel-load on the ground is spectacularly dangerous.) Repeat the fires twice a year, at the Spring and the fall of the leaf, right after a soaking rain, Native-style. Show the results to the world in ten years, at Autumn’s strawberry time. Continue indefinitely.

But where? How about the dead center of Myles Standish State Forest in southeastern Massachusetts?

DATES & CALENDRIC DIFFERENCES

The Julian Calendar has a tiny yet insidious flaw. Only over the centuries did it become apparent.

A year is not exactly 356.250000 days long , it is 365.242375 days long (even more insidious: that number changes slightly, in non-linear ways). It was nothing you could feel. But after centuries, the calendar was lagging behind the astronomical calendar by 9 days in the 1500s. Pope Gregory fixed the calendar in 1582 with his worldwide reform via a Papal Bull. It involved zooming the calendar ahead 9 days, and then adding leap days using a new strict formula.

Many countries, though, were not buying it. They would lose nine days. Nine days of their lives! Nines days of rents! In the end, religion determined who did what: Protestant countries, such as England, stayed with the Old Style. Most of Catholic Europe adopted the New Style. By the 1600s, the Old Style calendar was 10 days off.

If that wasn’t bad enough, Gregorian calendar reform also moved New Year Day. It had to do with a proprietary way to calculate where Easter Sunday fell: why Christmas is always December 25 and why Easter has to bounce around is a testament to the odd length of the year, and to our odd tendency to impose arcane rules on ourselves. The old Julian calendar started the year on March 25. That is why September, October, November, & December were the 7th , 8th, 9th and 10th months, as their Latinate names imply. The New calendar now started on January 1st. This meant, for example, that February 10, 1602 Old Style was February 20, 1603 New Style (a different year).

Historians fix this by double dating: Feb. 10/20, 1602/3; or, Feb. 10, 1602 OS / Feb. 20, 1603 NS. Sometimes the new date was in a new month as well as a new year: Jan. 31, 1602 OS / Feb. 10, 1603 NS. In any case, all the dates out of England during this time (1602) are in the Old Style. Add ten days, and watch out for the change of months.

K.S., Gent.

******

Related Pages

|

|

||

|

Transatlantic Ways Before Pilgrim Arrival |

|

Click Here to dialogue Click Here to dialoguewith others about these subjects. |

|

| Back to Homepage | On to Time Line 3 |